PART TWO

TERRITORIAL DISPUTES

"INVOLVING MALAYSIA"

Territorial disputes in the Celebes Sea

Pulau Sipadan & Ligitan

TERRITORIAL DISPUTES

"INVOLVING MALAYSIA"

Territorial disputes in the Celebes Sea

Pulau Sipadan & Ligitan

SIPADAN dan LIGITAN

Sipadan and Ligitan are the only oceanic island in Malaysia, rising 600 metres (2,000 ft) from the seabed. It is located in the Celebes Sea off the east coast of Sabah. It formed by living corals growing on top of an extinct volcanic cone that took thousands of years to develop. Sipadan and Ligitan is located at the heart of the Indo-Pacific basin, the centre of one of the richest marine habitats in the world. More than 3,000 species of fish and hundreds of coral species have been classified in this ecosystem. Sipadan has been rated by many dive journals as one of the top destinations for diving in the world.

Hawksbill Turtle. Frequently seen in the waters around Sipadan and Ligitan: green and hawksbill turtles (which mate and nest there), enormous schools of barracuda in tornado-like formations as well as large schools of big-eye trevally, and bumphead parrotfish. Pelagic species such as manta rays, eagle rays, scalloped hammerhead sharks and whale sharks also visit Sipidan & Ligitan.

A turtle tomb lies underneath the column of the island, formed by an underwater limestone cavewith a labyrinth of tunnels and chambers that contain many skeletal remains of turtles that become lost and drown before finding the surface.

History. In the past, the islands were at the center of a territorial dispute between Malaysia and Indonesia. The matter was brought for adjudication before the International Court of Justice and, at the end of 2002, the Court awarded the island of Sipadan and Ligitan to Malaysia, on the basis of the "effective occupation" displayed by the latter's predecessor (Malaysia's former colonial power, the United Kingdom) and the absence of any other superior title. The Philippines had applied to intervene in the proceedings on the basis of its claim to Northern Borneo, but its request was turned down by the Court early in 2001.

On April 23, 2000, 21 people were kidnapped by the Filipino Islamist terrorist group Abu Sayyaf The armed terrorists arrived by boat and forced 10 tourists and 11 resort workers at gun point to board the vessels and brought the victims to Jolo. All victims were eventually released.

In his film Borneo: The Ghost of the Sea Turtle (1989) Jacques Cousteau said, "I have seen other places like Sipadan, 45 years ago, but now no more. Now we have found an untouched piece of art."

.

PULAU SIPADAN

PULAU LIGITAN

'

Ambalat Block

Ambalat is a sea block in the Laut Sulawesi which is currently in part of Indonesia sovereignty. Ambalat sea block is located off the coast of the Indonesian province of East Kalimantan (KALTIM) and south-east of the Malaysian state of Sabah. Malaysia refers to part of the Ambalat block as Block ND6 (formerly Block Y) and part of East Ambalat Block as Block ND7 (formerly Block Z). The deep sea blocks contain an estimated 62,000,000 barrels (9,900,000 mcubic) of oil and 348 million cubic meters of natural gas. Other estimates place it substantially higher: 764,000,000 barrels (121,500,000 mcubic) of oil and 3.96 × 1010 cubic meters (1.4 trillion cubic feet) of gas, in only one of nine points in Ambalat.

Sovereignty dispute

Malaysia. The dispute over the Ambalat stretch of the Celebes Sea began with the publication of a map produced by Malaysia in 1979 . Showing its territorial waters and continental shelf. The map drew Malaysia's maritime boundary running in a southeast direction in the Celebes Sea from the eastmost point of the Indonesia-Malaysia land border on the eastern shore of Sebatik island, thus including the Ambalat blocks, or at least a large portion of it, within Malaysian territorial waters. Indonesia has, like the other neighbours of Malaysia, objected to the map.

Indonesia. Indonesia had since 1959 claimed the islands of Sipadan and Ligitan, which in 1979 Malaysia included to be its archipelagic basepoints and again in June 2002. This effectively put the entire Ambalat area within its internal waters. During the International Court of Justice (ICJ) case over the sovereignty of Sipadan and Ligitan islands, Indonesia argued from the perspective of historic bi-lateral Agreements between Britain and the Netherlands over the issue of possessions. Indonesia quoted Convention between Great Britain and the Netherlands Defining the Boundaries in Borneo, June 20, 1891., Article IV:

"From 4° 10' North latitude on the east Coast the boundary-line shall be continued eastward along that parallel, across the Island of Sebittik (Sebatik): that portion of the island situated to the north of that parallel shall belong unreservedly to the British North Borneo Company, and the portion south of that parallel to the Netherlands."

and the Agreement between the UK and the Netherlands relating to the Boundary between the State of North Borneo and the Netherland Possessions in Borneo, September 28, 1915: Article 2:

"Starting from the boundary pillar on the West coast of the island of Sibetik, the boundary follows the parallel of 4° 10' North latitude westward until it reaches the middle of the channel, thence keeping a mid-channel course until it reaches the middle of the mouth of Troesan Tamboe. (3) From the mouth of Troesan Tamboe the boundary line is continued up the middle of this Troesan until it is intersected by a similar line running through the middle of Troesan Sikapal; it then follows this line through Troesan Sikapal as far as the point where the latter meets the watershed between the Simengaris and Seroedong Rivers (Sikapal hill), and is connected finally with this watershed by a line taken perpendicular to the centre line of Troesan Sikapal."

This was duplicated in the 1928 Dutch British Borneo Convention and the Dutch-British Agreement of 1930. Indonesia maintains the argument of these historical established agreements, namely: the Indonesia-Malaysia maritime boundary continued as a straight line along the 4° 10' North after it left the eastern land boundary terminus on the eastern shore of Sebatik Island. The Dutch-British agreements effectively placed the entire Ambalat Block as within Indonesian territorial waters.

This was duplicated in the 1928 Dutch British Borneo Convention and the Dutch-British Agreement of 1930. Indonesia maintains the argument of these historical established agreements, namely: the Indonesia-Malaysia maritime boundary continued as a straight line along the 4° 10' North after it left the eastern land boundary terminus on the eastern shore of Sebatik Island. The Dutch-British agreements effectively placed the entire Ambalat Block as within Indonesian territorial waters.

Indonesia lost the ICJ case on the issue of "effective occupancy", which was considered to over-rule the established agreements and the two islands were awarded to Malaysia. Indonesia argues Malaysian oceanic territory extends only 10 nautical miles (19 km) from Ligitan and Sipadan in accordance with UNCLOS, and that not only the 1979 Malaysian map is not only outdated and self-published, ASEAN rejects it and it severely impinges the oceanic rights of Thailand, Vietnam, China and the Phillipines.

Indonesia claims the Ambalat region pursuant to the 1982 UN Common Law of the Sea, under Articles 76 and 77. Takat Unarang ("Unarang End Point/Outcrop") is the nearest to land territory at stake in the dispute, but at best, at low-tide elevation is more a rocky outcrop than a large island, but still meets the meaning of Article 121 of the LOSC. Takat Unarang is 10 nautical miles (19 km) from Indonesia’s low-water line or ‘normal’ baselines, and thus in line with Article 13 of the LOSC dealing with low-tide elevations. Takat Unarang is 12 nautical miles (22 km) from the nearest point on Malaysia’s loq-water line. However, Malaysia contends on occasion Takat Unarang is no more than a submerged rock and therefore not a valid basepoint for generating maritime claims to jurisdiction.

Effect of ICJ Ruling on Sipadan and Ligitan Islands. In late 2002, the ICJ awarded the two islands to Malaysia based on 'effective occupation' (effectivitès) rather than de jure ruling. The ICJ decision had no bearing on the issue of the Indonesia-Malaysia maritime boundary in the disputed area of the Sulawesi (Celebes) Sea.

Following the ICJ loss, Indonesia amended its baseliens, removing Sipadan and Ligatan islands as basepoints. In 2008, Indonesia redrew baselines from the eastern shore of Sebatik Island to Karang Unarang and three other points to the south-east. This results in the Ambalat Block no longer being entirely inside Indonesian internal waters.

However, any determination of the ownership of Ambalat would require the maritime territorial limits of two countries to be determined via bilateral negotiation. Furthermore, On June 16, 2008, Indonesia made a submission to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (UNCLCS) regarding its claim to continental shelf rights beyond 200 nautical miles (370 km) of its coast, whereby, in accordance with Article 76 of the UN Conventions on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) a coastal state has the right to delineate the outer limits of its continental shelf. UNCLOS, Article 77 ensures confirming maritime territory of a coastal state secures sovereign rights for exploration and exploitation, which "do not depend on occupation, effective or notional, or on any express proclamation". Indonesia is the 12th state to submit its Extended Continental Shelf (ECS) claim, the first being the Russian Federation, which submitted one in 2001. Malaysia submitted its claims jointly with Vietnam in May 2009.

Petroleum Concessions

Malaysia. On February 15, 2005, PETRONAS awarded two Production Sharing Contracts (PCS) to Shell and PETRONAS Carigali Sdn Bhd for the ultra-deepwater Blocks ND6 (formerly Block Y) and ND7 (formerly Block Z) off the east coast of Sabah, encroaching into Indonesian-claimed Ambalat.

The two blocks which are the main cause of the conflict are ND6 Block covers an area of about 8,700 square km, where partners will acquire and process 1,700 square km of new 3D seismic data and drill three wildcat wells with minimum financial commitment for the block at US $37 million. ND7 Block has an area of about 17,000 square km. Partners will acquire and process 800 square km of new 3D seismic data and drill one wildcat with minimum financial commitment for the block at US $13 million.

Shell and PETRONAS Carigali were to jointly operate both blocks. Shell has 50 per cent working interests; split between Sabah Shell Petroleum Co Ltd (40 per cent) and Shell Sabah Selatan Sdn Bhd (10 per cent). PETRONAS Carigali: was to own the remaining 50 per cent.

Indonesia. Indonesian awards predate the Malaysian PCS awards by at least one year. ENI SpA of Italy was awarded Ambalat Block (overlaps Malaysian ND6) in 1999 and US company Unocal the East Ambalat Block (overlaps Malaysian ND7) in 2004.

Incidents

One response prompted by the Sipadan and Ligitan case has been a lighthouse-building campaign. Indonesia has announced its intent to construct 20 lighthouses in the Ambalat area alone. Construction of a light beacon on Batuan Unarang on the fringes of the disputed zone was interrupted by Malaysian forces at the outset of the dispute on 20 February 2005, when Indonesian construction workers were arrested and later released.

The dispute between the two South-East Asian nations amounted to a minor skirmish between the two navies several times. In March 2005, Indonesia accused the Malaysian navy vessel, KD Renchong, of ramming its military ship, KRI Tedung Naga. The incident caused minor damage to both vessels. A few days after the incident, Indonesian Defense Minister Juwono Sudarsono alleged that the Malaysian government had sent an apology regarding the incident. The Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister of Malaysia, Najib Razak however denied making any apology. Subsequently Kompas agreed that their report is inaccurate and retract the story and Malaysia agreed not to take action on their misreporting.

Indonesia has submitted 36 diplomatic notes of protest to Malaysia over violations of disputed territory since 1980.

In June 2009, the dispute was reignited when Indonesian lawmakers met the Malaysian Defense Minister and accused Malaysia of violating Indonesia's maritime boundary by entering the disputed waters 19 times since the month of May 2009. On May 25, 2009, Malaysian Navy and coastguards at the Ambalat were ordered to leave Ambalat waters by the Indonesian sea patrol KRI Untung Suropati. Malaysian fast-attack vessel KD Yu-3508 (Malaysian navy boat) on 04.03.00 LU/118.01.70 East Longitude position, and entered Indonesia territory at 12 nautical miles (22 km), clearly violating the UNCLOS on sea border territory. Lt. Col. Toni Syaiful, commander of the Eastern Fleet stated, "“[Despite] being warned twice, they just moved away several meters. Eventually, the commander of KRI Untung Suropati, Capt. Salim, made the decision to assume combat readiness. Only then did the Malaysians decide to flee.” Later on the Chief of Malaysian Navy apologized for the provocation by his forces, and denied the claim that a Scorpene Class Submarine of RMN operate in the disputed territory or near the Indonesian Island of Sulawesi.

Indonesia had stationed 7 of 30 capital combat ships of the Eastern Fleet Command on active notice in the area, according to Indonesian Navy Chief Adm. Tedjo Edhy Purdijatno

l

.

The Sulawesi Sea Situation: Stage for Tension or Storm in a Teacup?

Mark. J. Valencia and Nazery Khalid

Mark. J. Valencia and Nazery Khalid

The Ambalat (Indonesia)/ ND6-ND7 (Malaysia) boundary dispute in the western Sulawesi Sea has resurfaced with a vengeance threatening to disturb Indonesia-Malaysia relations. The issue has high stakes because a deepening of the dispute could create instability in the region and undermine ASEAN unity. What’s all the fuss about and why now?

The area has been militarized. Indonesia has six warships and three warplanes in the area while Malaysia has several navy and coast guard vessels and aircraft there. Incursions by both sides into each others claimed waters have become increasingly frequent since the beginning of this year. Malaysia put bilateral talks on hold in April 2008. Things came to a boil on May 25 when an Indonesian navy vessel reported that it was only moments away from opening fire on a Malaysian warship that had allegedly encroached on claimed Indonesian waters. Some speculate that officials in Indonesia were using the incidents to pander to the Indonesian public in the run-up to the July 8 Presidential election. The Indonesian media certainly played up the saber rattling sound bites by Indonesian officials. Indonesian Defence Minister Juwono Sudaryono said “We are undeterred. Let Malaysia send military force and launch propaganda in Ambalat …“ An international relations expert said, “I am supportive of deploying Indonesian warships to Ambalat”. Weighing in on the dispute in a rather alarming tone, Vice President Jusuf Kalla said Indonesia must take action and be prepared to wage war.

July 6 protest over Ambalat by the Betari Brotherhood Forum in front of the Malaysian Embassy in Jakarta

However, cooler heads prevailed. Indonesia sent a diplomatic note to soften the situation and dampen the fiery response. And in an attempt to reduce tension, six leading Indonesia legislators traveled to Malaysia to try to convince their counterparts in Malaysia of the seriousness of the problem. Moreover the Malaysian Navy Chief apologized to Indonesia for its actions there.

But why did this issue bring these two normally “brotherly” countries to this point ? What are the prevailing circumstances that have contributed to the rising temperature between Kuala Lumpur and Jakarta on this seemingly minor issue?

The Background: Conflicting Claims

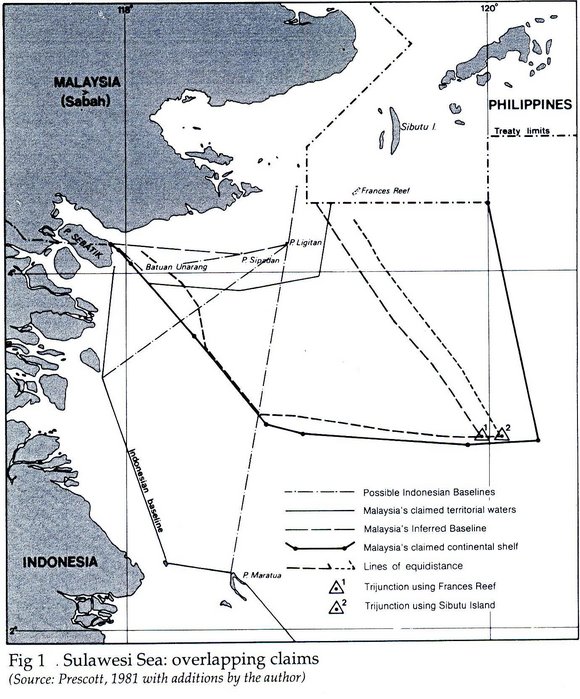

Malaysia’s inferred baseline, which links its territory on Sebatik Island with Pulau Sipadan does not connect islands fringing its coast nor does it enclose a coast which is deeply indented, and it deviates appreciably from the general direction of the coast. Thus to Indonesia the baseline does not appear to conform to the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which both Malaysia and Indonesia have ratified.

Malaysia’s inferred baseline, which links its territory on Sebatik Island with Pulau Sipadan does not connect islands fringing its coast nor does it enclose a coast which is deeply indented, and it deviates appreciably from the general direction of the coast. Thus to Indonesia the baseline does not appear to conform to the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which both Malaysia and Indonesia have ratified.

Instead, Indonesia sent a diplomatic note to soften the situation and dampen the fiery response. And in an attempt to reduce tension, six leading Indonesia legislators traveled to Malaysia to try to convince their counterparts in Malaysia of the seriousness of the problem. Moreover the Malaysian Navy Chief apologized to Indonesia for its actions there.

Figure 1: Overlapping claims in Sulawesi Sea

Malaysia has unilaterally drawn the common territorial sea boundary as a line which bisects the angle formed by Indonesia’s archipelagic baseline and Malaysia’s inferred baseline (see Figure above). Indonesia argues that such a line totally ignores Batuan Unarang, a rock whose presence entitles Indonesia to claim territorial seas. Malaysia owns the islands of Sipadan and Ligitan. But it also claims territorial seas and a section of continental shelf from these features which extend beyond a line of equidistance with Indonesia. A length of the boundary claimed by Malaysia does closely follow an equidistant course, but it extends too far to the southeast, discounting Pulau Maratua, a feature forming part of Indonesia’s archipelagic baseline.

In the western margin of the sea, the Malaysian continental shelf claim encloses the edge of the onshore/offshore petroliferous Tarakan basin and cuts completely in half the closure of a two-kilometer thick offshore sediment pod extending to the southeast. Indonesia had originally leased a portion of this area that it calls Ambalat to Scepter Petroleum Ltd. Just one of the Ambalat blocks is estimated to contain as much as 764 million barrels of oil and 1.4 trillion cubic feet of gas. If Sipadan and Ligitan were ignored, an equidistance line between Indonesia’s archipelagic baselines and Malaysian territory would give more of this petroliferous basin to Indonesia.

The Ambalat dispute originated in 1979, when Malaysia published its ‘Peta Baru’, or literally ‘new map’. However, it was greatly exacerbated in 2002 when the International Court of Justice (ICJ) awarded Malaysia both Sipadan and Ligitan. The ICJ made no decision on whether the features should be able to claim maritime zones, nor on maritime boundaries. But Malaysia then used these features as base points to make further claims to territorial sea, EEZ and continental shelf. Making matters worse, in February 2005 Malaysia granted oil exploration sights to Shell Oil Company and to its national oil company Petronas in the disputed area that overlapped areas Indonesia had previously granted to ENI in 1999 and to UNOCAL in 2004(Figure 2).

Figure 2: The Ambalat/N6-N7 Dispute

The decision of ICJ in 2002 to award sovereignty of Sipadan and Ligitan to Malaysia shocked and inflamed Indonesia national sentiment. It also affected the careers of some officials who had agreed with Malaysia to take the case to the international court on a “winner takes all” basis. For Malaysia, this was a case of ‘winning the battle but losing the ‘war’. The Indonesian government vowed this would never happen again and indeed it has refused to take the Sulawesi Sea issue to the Court or any third party arbitration. Given this experience and the negative public mood, Indonesia is also highly unlikely to grant any concessions to Malaysia in this or other boundary negotiations. Indeed it has insisted that the Ambalat dispute be negotiated together with other outstanding boundary disputes with Malaysia, including the EEZ North of Tanjung Datu, the third party point south of Singapore’s newly won Pulau Pedra Branca, and the EEZ boundary in the Malacca Strait. This is an attempt to force Malaysia to yield on the Ambalat issue and claim only territorial seas around Sipadan and Ligitan.

The ICJ judgment came at a time when Indonesia was facing secessionist movements in West Irian and Acheh and thus poured political salt into a gaping wound in the Indonesian national psyche. Indeed this loss fueled a national paranoia regarding the erosion of unity of the nation. In the past, maritime security and its importance in foreign policy did not shine prominently on the political radar of the Jakarta elite. However, the judgment by ICJ on Sipadan and Ligitan in favor of Malaysia marked a major elevation of maritime matters among Indonesia’s political class. Indonesia’s perspective on Ambalat is also shaped by its archipelagic viewpoint that to quell maritime security threats coming from piracy, smuggling and potential acts of terror, it needs to better control its maritime domain. To Indonesia, the ICJ decision in favor of Malaysia on grounds of ‘continued exercise of authority’ over the islands was particularly difficult to accept as they are located south of what Jakarta considers its baseline for determining its maritime boundary with Malaysia. The ‘loss’ of Sipadan and Ligitan was a painful reminder to Indonesia of the heavy price to pay for not attending closely to maritime issues. Indonesia’s determination not to repeat the bitter lesson of Sipadan and Ligitan is arguably reflected in is conduct regarding the Ambalat dispute.

The intensity of the Ambalat dispute belies the otherwise close practical cooperation between Malaysia and Indonesia in the maritime realm. Both nations have been engaged in bilateral coordinated naval patrols called MALINDO to secure the Straits of Malacca from trans-national threats such as piracy. Both also participate in trilateral patrols with Singapore called MALSINDO. There are also increasing communications between maritime coordination centers on the Indonesia side at Belawan and Batam, and Malaysia’s in the naval town of Lumut. Both countries, along with Singapore, have announced the formation of a ministerial level tripartite forum to discuss and improve maritime security in the Strait of Malacca. Given this history and degree of cooperation, and the close socio-economic and cultural ties between the two countries, it is deeply regrettable that they have come to loggerheads over this boundary dispute.

The Way Forward: Towards amicable settlement of the dispute

For the time being, Malaysia has proposed that patrols be suspended to avoid further incidents, while Indonesia has proposed joint patrols of the area, also urging Malaysian vessels and aircraft not to come too near its claimed area. This will have to be sorted out at the next negotiating session between Kuala Lumpur and Jakarta in July 2009. They might also change their patrols from those being conducted by the military to the Coast Guard or marine police to try to avoid conflict. Meanwhile the two neighbors and long term friends should abide by their Incidents at Sea Agreement (INCSEA) which states that their warships and military aircraft should avoid the use or threat of force against one another. It also provides standard safety procedures when encountering each other’s ships and aircraft. Calls by both sides to refrain from provocation and to observe the rules of engagement should be heeded to prevent exacerbating the dispute.

Ultimately there may be room for a co-operative solution like joint development, as practiced between Malaysia and Thailand in the Gulf of Thailand, although given the recent history the sharing may have to be largely in Indonesia’s favor. Until such a solution is implemented, it is hoped that this seemingly small issue will not disturb Malaysia-Indonesia relations and peace in Southeast Asia. The relationship between the two is too close and precious to be soured over this issue. Hence both parties must work hard to contain the dispute and settle it amicably for the sake of preserving bilateral ties and regional stability.

To this end, the recent conciliatory tones coming from Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur to defuse tensions over Ambalat give hope that good sense and cool heads will prevail between the parties. This augurs well towards mending the strained ties over the issue and returning them to a more stable course that befits the exceptionally cordial relationship between their highest political echelons – despite the historical baggage between them and occasional bluster over issues such as illegal immigrants and abuse of maids – and the close socio-economic and cultural ties between their peoples. However, Malaysia and Indonesia will have to work hard to quickly repair damaged relations lest they fester. Even the closest of ties can easily break if they are continuously stretched.

Mark J. Valencia is a Visiting Senior Fellow and Nazery Khalid is a Senior Fellow at the Maritime Institute of Malaysia. They wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

.

Bandar Limbang

LIMBANG DISPUTE

The dispute over Limbang district arose from the annexation of the district by Sarawak's Rajah Charles Brooke in 1890. The "involuntary cession" resulted in Brunei being split into two - the main part with three districts (Brunei, Muara, Tutong and Kuala Belait) to the west of Limbang, and the Temburong district to the east of Limbang.

The de facto boundary ran along the watershed between the Brunei River and Limbang River basins on the western side of the district, and along the length of the Pandaruan River on the eastern side. Boundary agreements have delineated a stretch of the western order and the Pandaruan River while the other stretches have yet to be delineated.

The two countries agreed, via the signing of Exchange of Letters on 16 March 2009, to settle their boundary issues and demarcate their common border according to the five historical agreements, of which two directly concern Limbang, and to use the watershed principle to fill in the gaps. This essentially reaffirms the current de facto boundary without major deviation and has led Malaysia to declare that the Limbang Question has been settled with Malaysia having unequivocal ownership over Limbang. Brunei however immediately denied Malaysian press reports after some members of the Brunei public demanded clarification regarding the matter on the local 'Have Your Say' online forum, saying the Limbang Question was never discussed during negotiations for the Letters of Exchange. Malaysia subsequently said the Limbang Question will be settled when the survey and demarcation of the boundary between the two countries is completed.

Follow up.....

Follow up.....

BANDAR SERI BEGAWAN, 17 March 2009: Brunei has officially dropped its long-standing claim over Sarawak’s Limbang district after the two countries resolved various land and maritime territory disputes.

“Brunei has decided to drop the Limbang issue and as a result, Limbang is part of Malaysian territory,” Prime Minister Datuk Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi announced to Malaysian media.

The resolution of the disputes were sealed via the signing of the Letters of Exchange by Abdullah and the Sultan of Brunei Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah at Istana Nurul Iman here yesterday

The other disputes include over where the maritime boundary between the two countries in the South China Sea should run, the rights to exploit potentially rich oil deposits in the disputed maritime territory, the right of movement by Malaysian vessels over Brunei waters and the demarcation of the common boundary of the two countries.

The dispute over Limbang can be traced back to the cession of the territory by Brunei to Sarawak’s White Rajahs in 1890. The cession had been strongly disputed by the Sultanate which regarded the transfer as annexation by Sara-wak.

Yesterday, Abdullah thanked the Sultan for the resolution of the various disputes, especially that of Limbang.

He said bilateral relations between the two countries would now enter a new era.

Abdullah and the Sultan said in a joint statement that they had reached agreement over themaritime boundaries between the two countries in the South China Sea.

Bandar Limbang

PETALING JAYA, 19 March 2009: Brunei has denied that it has dropped its claim on Limbang in Sarawak. It says the issue was not even discussed at last Monday’s (17 March) deliberations between the two countries.

Both the Brunei-based papers, The Borneo Bulletin and the Brunei Times Wednesday (18 March) quoted Pehin Orang Kaya Pekerma Dewa Dato Seri Setia Awg Lim Jock Seng, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade II, as saying claims on Limbang were never discussed during Monday's deliberations between Brunei and Malaysia.

He was responding to YB Dato Paduka Hj Puasa bin Orang Kaya Seri Pahlawan Tudin's query on the contents of the "Letter of Exchange" signed between Brunei and Malaysia, which also touched on Brunei's claims over Limbang at the Legislative Council meeting Tuesday (16 March).

Pehin Lim said there were certain press reports Wednesday claiming that Brunei has dropped claims over Limbang.

"In actual fact, the claim on Limbang was never discussed. What was discussed was the demarcation of land boundaries on the whole," he said.

"The joint press statement issued Wednesday (17 Mar) mentioned that the demarcation of the land boundaries between the two countries will be resolved on the basis of five existing historical agreements between the Government of Brunei and the State of Sarawak, and, as appropriate, the watershed principle.

"After that a working group comprising general surveyors of the two countries will follow with the technical aspect to solve the land border issue," Pehin Lim added.

His Majesty the Sultan and Yang Di-Pertuan of Brunei Darussalam and Malaysian Prime Minister Dato' Seri Abdullah Haji Ahmad Badawi held a four-eye meeting at the Istana Nurul Iman on Monday and signed the Exchange of Letters to mark the successful conclusion of negotiations.

The negotiations have been ongoing for many years on outstanding bilateral issues between the two countries with regard to historical, legal and other relevant criteria involving both sides, the reports said.

The reports said that both sides noted the agreement of their respective governments on the key elements contained in the Exchange of Letters, which included the final delimitation of maritime boundaries between Brunei Darussalam and Malaysia, the establishment of Commercial Agreement Area (CAA) on oil and gas, the modalities for the final demarcation of the land boundary between Brunei Darussalam and Malaysia and unsuspendable rights of maritime access for nationals and residents of Malaysia across Brunei's maritime zones en route to and from their destination in Sarawak, Malaysia provided that Brunei's laws and regulations are observed.

In a separate report, the Borneo Bulletin said local media was not allowed into the press conference called by the Malaysian Prime Minister.

“Local media representatives were earlier barred from attending the press conference. The visit itinerary didn't state it was an exclusive affair,” the report said.

“The exclusive press briefing held for the Malaysian media in Brunei on Monday following the signing of Letters of Exchange (LOE) apparently generated the latest controversy over Limbang.”

It said the issue about Brunei dropping its territorial claim on Limbang has caused a stir among members of the public as questions are being asked over the veracity about this claim.

“Malaysian media have widely reported Prime Minister Datuk Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi as saying that Brunei has dropped its claim on Limbang. This statement was made at a press conference on Monday at the Malaysian High Commission exclusively for the Malaysian media.”

It said though no official copies of the LOE were made available, the five main points that were highlighted mostly involved the demarcation of boundaries between the two countries and that the Malaysian media quoting their Prime Minister reported that Brunei has decided to give up all claims on Limbang.

“What is rather puzzling in hindsight is about why the Brunei media was not permitted to cover the press briefing. When Borneo Bulletin as well as state media persons went to cover the press conference, they were politely shunted out saying that it was 'exclusive' for the Malaysian media,” the report said. (MySinchew)

Sunday May 9, 2010

A tale of two oil blocks

BY LEONG SHEN-LI

The 2009 agreement between Malaysia and Brunei over territorial dispute has come under intense criticism for supposedly putting the former at a disadvantage. But is the picture being painted the correct one?

THE historic Exchange of Letters between Brunei and Malaysia, which ended two decades of territorial dispute between the two countries, was controversial from the day one.

Reporters who covered the March 16 event in Brunei last year and had filed their stories with their respective papers were stumped on their flight home – headlines like “Brunei denies Malaysia’s Limbang story” and “Limbang issue never discussed” were splashed across Bruneian newspapers available on the plane.

Just two days before, then Prime Minister Datuk Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi had signed the Exchange of Letters (essentially an agreement between countries) and had proudly told newsmen that Brunei had dropped its claim over Limbang in Sarawak as a result of the agreement.

But the Bruneian newspapers, quoting Brunei’s Foreign Affairs and Trade Minister II Pehin Lim Jock Seng, effectively denied Abdullah’s version of the agreement.

A little more than a year later, the agreement is still creating controversy.

This time, not only is the status of Limbang being questioned. The other major point of the agreement, that concerning the dispute over maritime territories, beneath which could lie billions of ringgit worth of oil and gas, is also being scrutinised.

The severe lack of information concerning the agreement has created opportunities to fan confusion and emotions among Malaysians. But thanks to the recent prodding by Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, the Government has been forced to let more details out into the public domain.

With the information now available, it may be possible to see if Malaysia has benefited from the deal, or otherwise.

Let’s deal with the Limbang issue first. Brunei’s Lim was right to say that nowhere in the 2009 agreement was the word “Limbang” mentioned.

Reacting to Brunei’s denial, Datuk Seri Dr Rais Yatim, who was then Foreign Minister, confirmed that Limbang was not mentioned in the agreement.

“But what was agreed to was for five historical border treaties between Brunei and Sarawak to be adhered to. This effectively makes the Limbang issue no more,” he said.

Two of the five treaties – one signed in 1920 and the other in 1933 – directly concerned Limbang. They established the border between Limbang and Brunei where it is today. As the border now places Limbang inside Malaysia, Brunei’s act of agreeing to follow the two agreements effectively means it agreed to let Limbang remain Malaysian. Once the demarcation of the border is completed, Limbang would be without question part of Sarawak.

So why the initial uproar by Brunei? One view is that it was not too happy with Malaysia quickly saying that it had got Limbang. It is extremely sensitive to the Bruneians as its loss in 1890 resulted in the Sultanate being split into two parts.

“Furthermore, they did not go around thumping their chests saying that they now got the oil that we wanted,” one commentator said. Nevertheless, he pointed out that Brunei’s Lim did not actually deny the statement that the Sultanate had dropped its claim over Limbang, indicating that there is no doubt that the claim had been dropped.

One of the points raised recently was whether Limbang was worth trading for the two oil-rich blocks. While the suggestion of such an exchange is wrong to begin with, the importance of Malaysia getting the isolated Limbang district should still not be downplayed.

A rather interesting but possibly exaggerated scenario was given by a historian. Brunei’s claim over Limbang, he pointed out, is based on the “unfair treaty” of 1890 between its Sultan and the White Rajahs of Sarawak.

“Brunei lost Limbang in an unfair treaty. But there is a school of thought that all treaties between the White Rajahs of Sarawak and Brunei, which resulted in Brunei losing the whole of Sarawak and the west coast of Sabah, were also unfair.

“After Limbang, could Kuching – or Kota Kinabalu for that matter – be claimed?” he queried.

Maritime territorial claims

Let’s move on to the maritime territorial claims and the two oil blocks.

Malaysia’s claim over the stretch of South China Sea where the two oil-rich exploitation blocks – named Blocks L and M by Malaysia (but were named as Blocks J and K by Brunei) – are located, and which Brunei claims to be its exclusive economic zone, has been described as akin to a person claiming ownership of the front yard of his neighbour’s house.

In 1979, Malaysia published a map showing its maritime territories. Whether rightly or wrongly, the map denied Brunei most of its territorial waters.

The UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (Unclos), of which both Brunei and Malaysia are signatories, gives all countries with coastlines the right to claim territorial waters up to a certain distance from the coastline. Malaysia’s 1979 map clearly did not conform to that provision as far as Brunei’s right to territorial waters was concerned.

It took four long days after the controversy blew up – after Abdullah and Petronas had issued statements – for Malaysia’s Foreign Ministry to state unequivocally that Malaysia’s dropping of its claim over the two oil blocks and the rest of Brunei’s territorial waters was based on sound international law.

There was no “signing away” of the two blocks because Malaysia could never have owned them in the first place. It would now seem unlikely that the two blocks could have been a major bargaining chip for Malaysia to get Limbang.

Malaysia awarded a concession over the two blocks to Petronas Carigali and Murphy Oil in 2003 as an assertion of its claim over the area, just as Brunei awarded concessions to six international companies to assert its claim over the same area.

But because of the dispute over sovereignty, none of the companies could start drilling for anything.

In March 2003, Murphy’s boat was chased away by a Bruneian gunboat and the following month, the Malaysian navy sent several gunboats into the area to block the arrival of a ship owned by Total, one of the companies awarded the concession by Brunei.

It was clear that not a drop of oil or a whiff of gas could be extracted from the area without the deadlock being resolved.

For more than half of the duration of the dispute, Dr Mahathir was Prime Minister. Going by what he has been saying recently, it is no surprise that there was no breakthrough in negotiations during that time.

However, as the realisation that no one would gain if the deadlock continued, pressure to move on started mounting.

A senior diplomat familiar with the negotiations said one of the things which broke the deadlock was when Malaysia indicated that it was willing to “discuss” its claim over the disputed waters.

Compromises were made by both sides and, because of the spirit of neighbourliness and close cultural ties, the matter was finally settled in late 2008. Malaysia recognised Brunei’s ownership of the disputed waters while the legality of the land border between Sarawak and Brunei – with Limbang remaining in Malaysia – would no longer be raised again by Brunei.

Despite Brunei becoming the owner of the oil and gas from the two blocks, the 2009 agreement allowed Malaysia to jointly exploit the resources of the area for 40 years. Petronas has confirmed that it has been invited by Brunei to take part in the development of the area.

Unlike two other existing “sharing agreements” – that between Malaysia and Thailand, and Malaysia and Vietnam – the one with Brunei is unique. In the two earlier cases, sovereignty of the overlapping area is still in dispute but with Brunei, this issue has been settled.

The cake is Brunei’s but Malaysia’s got a significant slice of it. More importantly, after waiting for 20 years, the two countries no longer need to wait further to start eating it.

Leong Shen-li, the senior news editor in The Star, is one of the reporters who covered the signing of the Exchange of Letters. He also has a big fascination for border disputes.

1890: Brunei gives up Limbang to Sarawak’s second White Rajah Charles Brooke, splitting the Sultanate into two parts.

1979: Malaysia publishes map of its territorial waters. Map denies Brunei of any territorial waters in the South China Sea beyond the depth of 100 fathoms (182m), leaving Brunei with just a narrow strip of territorial waters, and claims the entire area beyond 100 fathoms as belonging to it.

1984: Brunei gains independence from Britain. It claims a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone which overlaps with the territorial waters claimed by Malaysia as shown in the 1979 map.

2003: Malaysia awards Petronas Carigali and Muphy Oil production contracts for the disputed Blocks L and M which lie within areas claimed by Brunei. Brunei also awards production contracts to Total, BHP Biliton and Hess for one block, and to Shell, ConocoPhilips and Mitsubishi for the other block.

March 2003: Brunei gunboats chase away Murphy Oil’s boat. One month later, Malaysian Navy gunboats prevent a Total boat from entering disputed area. All exploration work is suspended by both sides.

2009: Brunei and Malaysia sign Exchange of Letters to settle their land and maritime territorial disputes after more than 30 sessions of negotiations.

With the 2009 Exchange of Letters, Brunei and Malaysia agreed to establish their common border in two ways:

> By following five border treaties which were signed between 1920 and 1939.

> By filling the gaps not covered by the five treaties by following the “watershed” principle. This effectively means that there would not be any major deviation from the current border between Malaysia and Brunei. As Limbang is currently in Malaysian hands, there would be no change in its status once the demarcation process is completed.

1. The 1920 treaty establishes the eastern boundary of Limbang with Brunei along the entire length of the Pandaruan River.

2. The 1933 treaty establishes part of Limbang’s western boundary with Brunei along the watershed of the Brunei and Limbang Rivers “until a point west of Gadong Hill”.

3. The 2009 Exchange of Letters will fill in the gaps in the border according to the watershed principle.

No comments:

Post a Comment